From Survival to Healing: Understanding Trauma-Related Fragmentation and Dissociation

In the realm of trauma recovery, understanding the mechanisms of trauma-related fragmentation and dissociation is crucial. Without the presence of attuned and protective caregivers, young children are left to rely on their innate biological capacities to navigate the overwhelming landscape of a threatening world. The vivid recollections of constant fear, hunger, and loneliness shared by many trauma survivors underscore the dire need for coping strategies during these formative years.

The Brain's Role in Fragmentation

The human brain, with its inherent compartmentalization, is naturally predisposed to fragmentation, a process that becomes all too easy under the strain of traumatic experiences. The division of the brain into the right and left hemispheres, each responsible for distinct functions and modes of processing, sets the stage for potential fragmentation. The right hemisphere, dominant in childhood, is attuned to nonverbal cues and emotional experiences, while the left hemisphere, which matures later, is tasked with language and chronological memory. The corpus callosum, the bridge facilitating communication between the two hemispheres, can be underdeveloped in trauma survivors, further complicating the integration of experiences and emotions.

Dissociation as a Survival Mechanism

Dissociation, a phenomenon where one may feel detached from their body or emotions, serves as a survival mechanism, allowing individuals to endure acute stress by numbing or disconnecting from the pain. This adaptive response, while crucial in moments of danger, can lead to long-term challenges in processing and integrating traumatic memories.

Signs of Dissociation in Daily Life

Dissociation can manifest in various ways, influencing one's ability to function and process emotions. Some common signs include:

Inconsistent Functionality: Being able to navigate some situations smoothly while feeling completely overwhelmed in others.

Overwhelming Emotions: Experiencing emotions that flood your consciousness, leaving little room for rational thought.

Sudden Reactions: Encountering intense physical or emotional responses that seem disproportionate to the situation at hand.

Feeling Out of Control: Frequently feeling that your actions and words are not under your conscious control.

Dominant Anxiety: Living in a state where anxiety overshadows every aspect of life.

Feeling 'Possessed': Experiencing moments where you feel as if someone or something else is controlling your actions.

Self-Harm and Substance Abuse: Engaging in self-harm or substance abuse as a means to cope with inner turmoil.

Conflict Between Survival and Despair: Having aspirations for the future while simultaneously harboring a desire to escape life's pain.

Bodily Disconnection: Feeling detached from or unable to control your physical self.

Indecisiveness: Struggling to make decisions, from the mundane to the significant.

Social Insecurity: Constantly doubting whether others accept or value you.

Trust Issues: Finding it hard to trust others or, conversely, trusting too readily.

Abandonment Fears: Being perpetually haunted by the fear of being left alone.

Emotional Turbulence: Feeling like your emotional state is constantly in flux, without a stable ground.

Depression and Self-Loathing: Being engulfed in deep depression or intense self-hatred.

Anger and Shame: Navigating life with underlying anger or being overwhelmed by shame.

The Structural Dissociation Model

The Structural Dissociation Model, developed by Onno van der Hart, Ellert Nijenhuis, and Kathy Steele, offers a framework for understanding how chronic trauma can lead to the development of distinct parts within the personality. These parts, including an "Apparently Normal Part" (ANP) focused on daily functioning and "Emotional Parts" (EPs) entrenched in trauma responses, operate with varying degrees of independence, often leading to internal conflicts and a sense of being divided.

Navigating the World with Fragmented Parts

Survivors of trauma may find themselves navigating a world where their parts are in constant negotiation. The ANP strives to maintain normalcy and functionality, while EPs react to triggers with fear, shame, or anger, often without the coherent integration of these experiences. This internal dissonance can manifest in a range of symptoms, from dissociative episodes to difficulties in decision-making and emotional regulation.

Recognizing and Working with Trauma-Related Parts

Identifying and acknowledging these fragmented parts can be a transformative step in the journey of healing. By understanding the roles and needs of each part, individuals can begin to foster internal communication and cooperation, leading to a more integrated sense of self. Techniques such as mindfulness, somatic therapies, Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing Therapy (EMDR) and the nurturing of the "C" qualities (calm, curiosity, compassion) can empower survivors to engage with their parts in a healing and constructive manner.

Navigating the Terrain of Structural Dissociation: A Personal Reflection

The journey through understanding and healing from trauma is deeply personal and complex, particularly when confronting the phenomenon of structural dissociation. This intricate process, where different parts of our personality emerge in response to past traumas, can manifest in various challenging ways in our daily lives. Recognizing these signs and learning to speak the language of parts can illuminate the path to integration and healing.

The Path Forward

The journey from survival to healing involves recognizing the adaptive nature of fragmentation and dissociation while developing strategies to gently integrate these parts into a cohesive whole. By embracing the complexity of their internal landscapes, individuals can move toward a future where trauma no longer defines their existence but informs their resilience and strength.

In this exploration of trauma-related fragmentation and dissociation, we uncover the innate capacities of the human mind and body to endure and adapt to adversity. As we delve deeper into understanding these mechanisms, we pave the way for more compassionate and effective approaches to healing from trauma.

Reflection Prompts:

Signs of Structural Dissociation

As you reflect on your experiences, you might recognize different aspects of yourself in the following descriptions. Acknowledging these signs is the first step towards understanding the fragmented parts of your personality:

Functionality Varies by Situation: Notice if there are specific contexts where you can function seamlessly and others where you struggle significantly.

Overwhelming Emotions: Reflect on moments when emotions seem to engulf your entire being, leaving little room for anything else.

Sudden Reactions: Think about times when you've had intense, almost reflexive physical or emotional responses to situations.

Feeling Out of Control: Consider instances where you felt powerless over your actions or words.

Dominant Anxiety or Depression: Are there periods where anxiety or depression seems to dictate the course of your life?

Self-Harm and Substance Use: Contemplate any patterns of self-harm or substance dependency that feel compulsive or uncontrollable.

Conflicted Existential Feelings: Reflect on having aspirations for the future while simultaneously harboring a desire not to live.

Memory Issues and Identity Confusion: Think about difficulties with memory or moments of questioning your core identity.

Try to attribute these feelings or behaviors to specific parts of your personality. This exercise isn't about judgment but about understanding the diverse aspects of your internal experience.

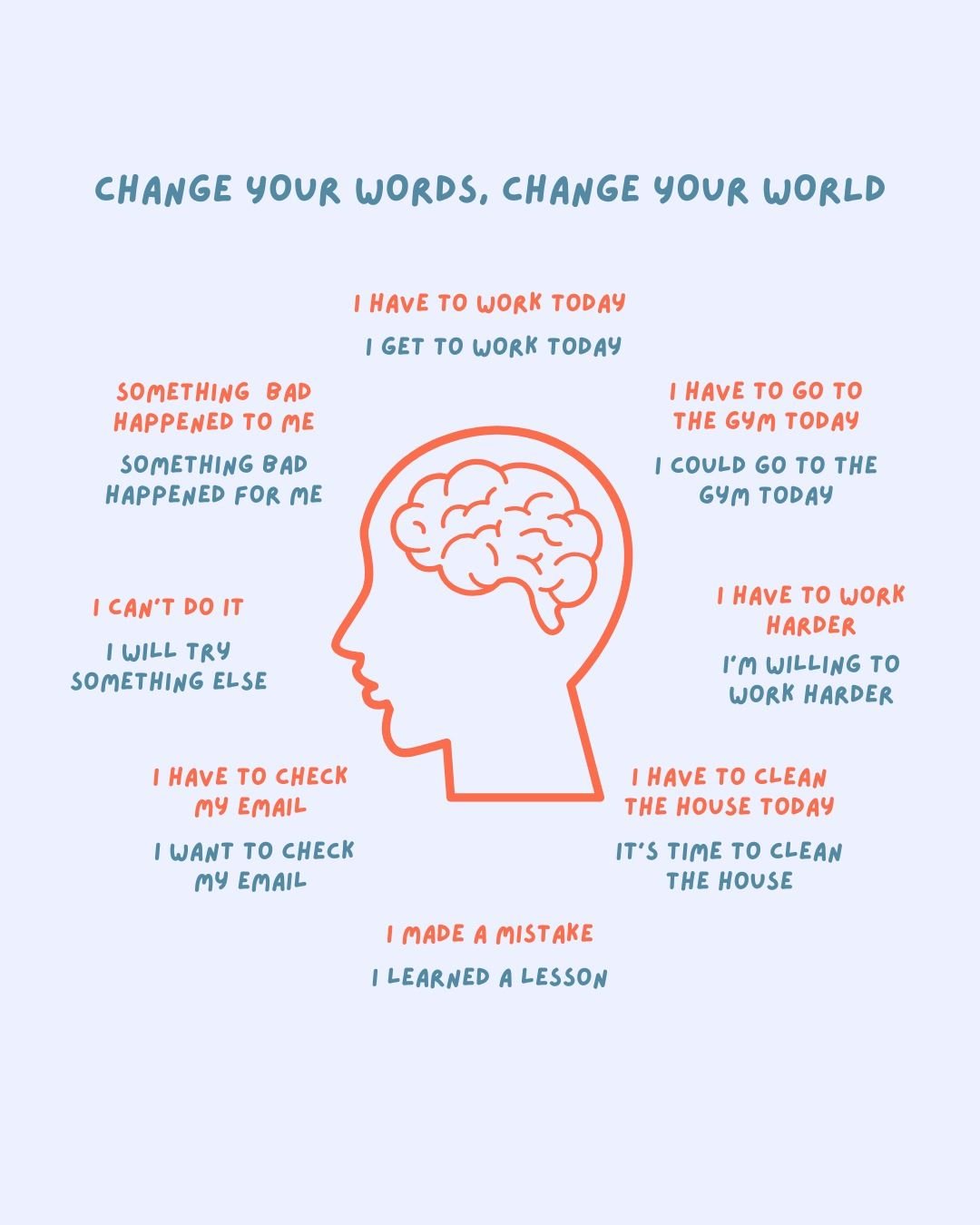

Speaking the Language of Parts

Transitioning to the language of parts can offer a new perspective on your internal dialogues. For each feeling or reaction listed below, try to translate it into parts language, which can help in distancing yourself from overwhelming emotions and fostering a sense of curiosity and compassion towards these parts:

“I’m depressed.” becomes "A part of me feels depressed."

“I am a failure.” transforms into "A part of me believes I'm a failure."

“I want to die.” shifts to "There's a part of me that doesn't want to keep living this way."

“It’s hopeless.” changes to "A part of me sees everything as hopeless."

“I’m worthless.” is reframed as "There's a part that feels worthless."

“No one loves me.” turns into "A part of me feels unlovable."

“I want to hurt myself.” becomes "A part of me thinks hurting myself might help."

“I’m fine.” shifts to "A part of me wants to believe I'm fine."

“I just need a stiff drink.” changes to "A part of me wants to escape through drinking."

Notice how expressing these thoughts in parts language affects your emotional response. Does it bring a sense of distance or clarity? Does it evoke compassion for these parts of yourself?

Strengthening Your “C” Qualities

Focusing on your “C” qualities—Curiosity, Compassion, Calm, Clarity, Creativity, Courage, Confidence, and Connection—can be transformative. Reflect on how these qualities manifest in your life and consider ways to enhance them. For instance:

Cultivate Curiosity by exploring new interests or asking more questions in your interactions.

Foster Compassion by practicing self-kindness and understanding towards yourself and others.

Enhance Calm through mindfulness practices or spending time in nature.

Develop Clarity by journaling or engaging in reflective conversations.

Boost Creativity by dedicating time to creative hobbies or problem-solving in novel ways.

Build Courage by facing small fears or advocating for yourself and others.

Strengthen Confidence by celebrating your achievements and acknowledging your strengths.

Deepen Connection by nurturing relationships and seeking out supportive communities.

Remember, any thought, feeling, impulse, or physical reaction that lacks these “C” qualities is likely a communication from a part. Recognizing this can help you approach these internal experiences with a sense of curiosity and compassion, facilitating a more integrated and resilient self.